Previous Project - An Historical Study of the Jesuit Enterprise in Zhili (Hebei) during the Qing

The journalist and radio broadcaster who became famous in the 1930s for her New York Tribune column, “On the record,” Dorothy Thomson, once said that, “Peace is not the absence of conflict but the presence of creative alternatives for responding to conflict.” Anthony Clark’s current project responds to the tragic conflict arising between China and the West, and seeks to use scholarly research and writing to, as Thomson suggests, formulate a “creative alternative for responding” to those frictions by analyzing Jesuit reports about imperial China and afterlife narratives generated during and after the Boxer Uprising. In our present context of China-West misunderstanding and tension, dedicated research on the trajectory of China-West relations will serve to elucidate the areas of conflict and confluence that have defined that long historical relationship. While the final product of this project – a scholarly monograph – is a principal aim, the anticipated impact of this project relates securely to the goal of better informing the academic and non-academic communities of the more common history of cohesion between China and the West. This scholarly study centers on the kernel from which Sino-Western relations emerged, which was the Jesuit missionary enterprise that served on the one hand as the first substantive encounter between Asia and European societies, and on the other hand a carefully constructed image of China that was adopted by Western intellectuals. Clark’s research and publications have examined the history of religious and diplomatic exchange between China and the West, and this project builds upon his previous work to better explain how the Jesuit missionary enterprise from the Enlightenment to the present has defined Sino-Western exchange within a representational archetype largely based upon martyrdom accounts generated to promote the causes of Christian saints. By centering my study on Jesuit descriptions of deaths and afterlives, he hopes also to help clarify how both cultures envisioned each other through text and aesthetics.

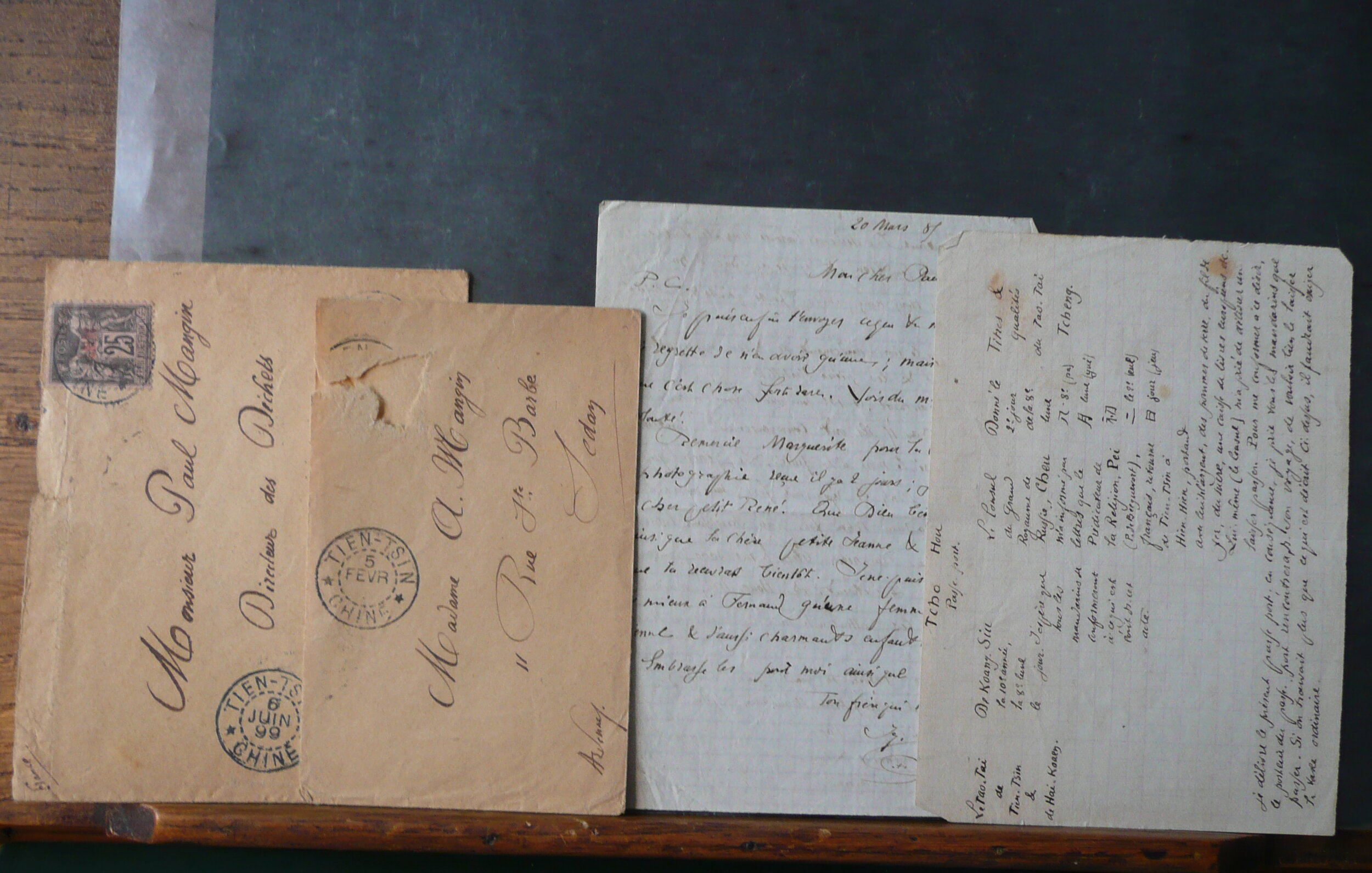

Behind this project is an observation of several recent decades of media and political strain between China and Western nations, and this research sets out to highlight the Jesuit “theater” of posthumous celebration of Christian martyrs who have served to influence the Western imagination of China. The main question this project considers is, what were the contours of Sino-Western religious and intellectual exchange from the Enlightenment to the twentieth century revolving around conceptions of death and afterlife? While most studies of China-West relations have centered on diplomatic history, nearly eighty percent of archival materials related to Western exchange with China are held in missionary collections; indeed, the first encounter China had with the West during the early modern era was with European Jesuits during the late sixteenth century. It is hardly known that during the first few centuries of Western diplomatic interaction with China, most of what European diplomats and academics knew about Asia was information given to them by Jesuits and other missionary orders. That China’s first dialogue with the West was in the religious domain is precisely why China’s present officials commonly reference Christianity when discussing other topics such as the question of national sovereignty, state negotiations, or even global trade.

To be even more precise about Clark’s current research: During the eighteenth century, the European enterprise of admiring China as a “more enlightened” analogue of the West was chiefly propelled by court Jesuits in Beijing, and appropriated by Enlightenment intellectuals such as Voltaire and Leibniz. After the conclusion of the Boxer Uprising, this Western attempt to represent China as both a perfect fit with Catholic Christianity (Jesuits) and a non-Christian alternative to the West (French Philosophes) had transformed into a missionary effort to appreciate only a Christianized Asia. Sino-Western conflicts such as the first Opium War and the Arrow War supplanted the Enlightenment imagination of an Asian “philosopher king” and replaced it with Western ambitions – diplomatic and missionary – to transform China into a Westernized and Christianized empire. My project thus traces the evolution of the West’s imagination of China from the theatrical Jesuit valorizations of the early Qing to the Jesuit mission in Western China during the late Qing that employed the celebration and canonization of Boxer era Christian martyrs to “canonize China” as an East Asian terra sancta.

This evolutionary curve of representing China changed from an imagination that privileged Chinese culture above the West into one that depicted Asia as a place in need of transformation and Christianization “through the blood of martyrs,” and their “afterlives” propounded through pro-Western narrative. Only one century after the Enlightenment, most (perhaps all) European nations viewed the West as culturally superior. This project shall help explain the underlying currents that led to the modern Western sense of cultural preeminence, one that largely finds its roots in the worldview shifts that took place in Europe between the Enlightenment and the collapse of imperial China. Looking at local Chinese and Vatican rituals of promotion and canonization connected with China’s Jesuit mission in Hebei province, as well as textual and aesthetic materials from the Qing era, Clark’s research explores how confreres of the Jesuit order reframed China within a new paradigm of Christian holiness to “redeem” it from the pejorative Western views promulgated after the close of the Enlightenment. By describing this long history of Sino-Western vacillation from mutual esteem to disagreement, and disagreement to esteem, the intellectual engine that drives modern decision-making will become more understandable. The Jesuit influence upon Western communications with Asia based largely upon Catholic martyrdom narratives will figure centrally in this project; our historical vision of China has been formed – some would say “created” – by Jesuit missionaries.